Staking as a fundamental building block for insurance

Hello and welcome to part three of Etherisc’s tutorial series. Today, we’ll start diving into the meaning and functionality of ‘staking’ in the context of decentralized insurance. In what is a complex topic, we’re dividing this tutorial into two. Here we will examine the general principals and applications of staking, with part two to follow and explore the more financial and technical details of staking as related to Etherisc.

Before reading on, please do also check out our tutorial Basics about the GIF framework. We’d highly recommend it as it provides an excellent overview of Etherisc’s platform, along with facts about insurance, parametric insurance, and much more.

The term ‘staking’ is used in abundance in the world of decentralized finance and blockchain, and so it’s worth exploring its different meanings before we dive into the specific use of the term in the domain of decentralized insurance.

We will discuss different types of staking, the advantages and disadvantages of each, and finally, how we use staking to coordinate various stakeholders in a decentralized insurance ecosystem. We also describe the current state of staking in Etherisc’s Generic Insurance Framework (GIF) and give an outlook on our planned next steps.

Mining

The origins of staking in decentralized finance stem from the use of staking in blockchain consensus algorithms. Let’s have a look at how the production (mining) of blocks in a blockchain works — in other words, how value is created in coins, gas, and transaction fees on a blockchain. Due to its decentralized nature, block production needs to be controlled and coordinated either through high effort (and energy) processes or other mechanisms, such as depositing collateral. If the production process was effortless, everyone would do it — opening the door for so-called ‘Sybil attacks’ which would leave the coins worthless. A Sybil attack is an attack on peer-to-peer networks by creating false identities. The attack can be aimed at influencing majority voting and network organization, slowing down the grid, disrupting networking, or intercepting communications between peers.

The two currently most popular ways to create blocks and avoid such an attack are proof of work (PoW) and proof of stake (PoS).

Proof of Work

The principle of proof of work is based on the idea that miners bundle transactions to blocks and prove that they have invested a certain amount of computational effort, which in turn is connected to energy consumption and therefore economic capital. This effort makes it prohibitively expensive for a single miner to take control of the network.

Proof of work typically means that the miner must calculate a verifiable block hash that meets predefined criteria. For this, the miner needs to systematically repeat these calculations with different so-called nonce (number used once) values. These calculations make mining a very computation-intensive process that requires specialized hardware and a lot of electrical power. For this reason, miners often join together in mining pools. Once a block is created, the miner or mining pool receives the transaction fees of the transactions contained in the block and a block reward in the form of the native coin of the blockchain, for example Bitcoin.

Proof of work is currently the predominant consensus method used by most major blockchains, including Bitcoin, its variants and layer 2 blockchains.

There are a lot of disadvantages connected to proof of work, starting with its vast energy consumption and associated ecological footprint. Additionally, there is also a tendency towards a form of centralization because only big players have access to the required specialized hardware needed to process a block, with the added fact that there is a monopoly of manufacturers producing this hardware.

Proof of Stake

Because of the apparent disadvantages of PoW, there has been extensive research on alternative consensus models. One method which solves most of the core problems raised by PoW, is proof of stake (PoS). In PoS, the validator (node) must deposit coins in a particular cryptocurrency if it wants to create blocks for that network, and the process of depositing coins is called ‘staking.’

Proof of stake networks use complex algorithms to determine the validator of the next block, and they need mechanisms to recover from different types of validator misbehavior. As in the case of successful PoW mining nodes, the selected validator nodes in a PoS network are rewarded with transaction fees and block rewards.

The more stakes a validator has, the more voting rights it has or the more of a say it has. You can compare this process to a public limited company or a cooperative: the more shares you own in the company, the more voting rights you have in decisions.

What is staking?

This all leads us to our discussion on staking. While originating from consensus research for blockchains, staking has become a fundamental primitive for decentralized finance (DeFi).

Staking crypto assets in the blockchain world is the process of actively participating in securing a blockchain-based protocol. So in staking, blockchain users lock their crypto assets as collateral for some protocol ‘value,’ thus ensuring the proper functioning of the protocol. The value could be some desirable property of the protocol, be it protection from sybil attacks, collateralization of a lending protocol, ensuring the compliant behavior of protocol participants, and so on. Because of its flexibility, staking has become a widely used primitive of many blockchain protocols.

Staking is always connected with a specific risk. Even if the protocol would not incorporate any risk, locking crypto assets for a certain time always incurs the risk of loss of value because of market price action. To compensate for the risk the stakers take, they receive rights and/or rewards.

Staking can be implemented in different ways. Participants contribute to a staking pool and receive rights and rewards directly, or they use an intermediary — the so-called ‘Delegated Proof of Stake’ (DPoS).

A special case of staking occurs with governance tokens. Governance tokens are blockchain tokens that grant voting and management power to their users. Some of you may have followed the vote regarding the listing of our DIP token (cryptocurrency of Etherisc) on Bancor. Here, all registered voters had the opportunity to participate in the decision. Many did too, and Bancor whitelisted our DIP token with almost 100% approval from the voters. Staking and governance in action!

Insurance — in a few words

Before we get into the details of the requirements for staking in the decentralized insurance domain and how our new implementation will meet these requirements, let’s look at the essential function of insurance.

While insurance could be described broadly as ‘a means of protecting against financial loss,’ the term is usually defined in much more detail. Insurance protects against financial loss, usually by pooling a large number of similar risks, thus spreading the risk across all those insured.

An example

Let’s have a look at fire insurance. We’ll make some assumptions to keep the numbers simple, in reality the numbers are different, but you’ll get the idea. If you own a house worth $100,000, there is an assumed risk of 1% per year that the house will burn down (that’s once in a century). Without insurance, if you want to make sure you always have a home, you need to have an additional $100,000 on top of the $100,000 you invested in the home to replace it in the event of a fire. This additional $100,000 may be challenging to come by, and it is very inefficient to have $100,000 in a bank account for an event that occurs on average only once in a century.

Step in insurance

If 1,000 homeowners pool their risks, there are 10 homes worth $1 million that will burn down each year based on an anticipated fire risk of 1%. So, each homeowner only has to pay $1,000 as a premium into a risk pool to cover that ‘expected loss’ (the $1 million divided by the 1,000 homeowners).

This works well as long as there are no conflagrations. In the worst-case scenario, if more than 10 homes burn down in a catastrophic event, the pool will not be able to cover that loss. Examples of such devastating events include wildfires, hurricanes, and other natural events, as well as pandemics, terrorist attacks, and other man-made events, also called ‘black swan events.’

So what to do? The answer is to ask investors to add risk capital to the risk pool.

Long-tail risks

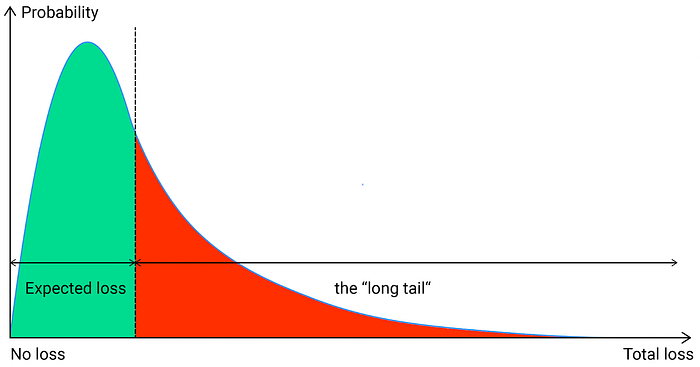

Suppose the probability of a conflagration burning down 100 homes is 0.1% per year (once every 1,000 years on average). The damage is $10 million. These high but implausible risks are also called ‘long-tail risks’ because they are represented by the ‘long tail’ of the risk distribution curve:

*Visualization of the '`long tail.’

In addition to the $1 million paid by premiums, you need another $9 million from investors. For example, they will charge a compound interest risk of, say, 5%, which equates to $450,000, so each homeowner would incur another $450. But with a total premium of $1,450, they are now insured not only against the typical risk of 10 burned homes per year but also against the risk of a once-in-a-millennium conflagration and everything in between.

Investors must commit their capital for the entire lifetime of the insurance policy because otherwise, they could move out of their capital as soon as there are signs that a ‘Black Swan event’ is becoming more likely. And, of course, the groups of insureds and investors could also overlap.

Traditional insurance features very high administrative fees on top of this lifelong $1,450 premium, which can be done away with by using decentralized blockchain-based insurance.

Staking for risk pools

Now, let’s outline the core features of Etherisc’s staking model and risk pools. You can study the model in more depth in our paper The Etherisc Staking Model, and we will dive into the topic even further in the upcoming part two of this blog.

The concept of risk pools

A risk pool is a smart contract that collects funds that are used to compensate for insurance claims.

In its simplest form, a risk pool could be a multi-signature that would be funded by some interested parties, be it investors or product owners. The risk pool is registered in the GIF (Generic Insurance Framework), approved by the Instance Operator and connected to one or more products that are registered in the same GIF instance.

The party which organizes the risk pool is called a ‘risk pool keeper.’ Premiums from purchase of policies are paid into the risk pool, and claims are covered from the funds of the risk pool. In this most simple form, investors have little control over their investments, therefore the risk pool and its keeper need to be trusted by the investors. To address this need, we have developed a concept that enables us to launch trust-free risk pools which can be operated in a decentralized way.

Trustless risk pools

For a trustless risk pool to function, methods must be implemented that technically and transparently guarantee that the interests of both insured and investors are met.

For the insured, this means that we can prove that the risk pool will always be able to fulfill claims.

For investors, this means that they will receive a fair share of the profits made, and that they can decide for which risks they will engage with their funds.

For both, this also means that the risk pool needs to be economically attractive for investors, without whom there may not be enough capital to enable the purchase of policies.

It is clear that it is challenging to design smart contracts which fulfill all of these guarantees, given that the amount of calculation involved on-chain needs to be limited.

While we expect that sooner or later, e.g. with the further rapid development of zero-knowledge-proofs, it will be possible to perform arbitrary complex, untrusted computations reliably off-chain and verify the results on-chain. This brings the need to devise a system which is somehow simplified, can be run fully on-chain and still meets the mentioned requirements.

We achieve this goal by using so-called ‘epochs.’ An epoch is a period of time that is typically a small fraction of the average period of a policy. For example, flight delay policies typically have a period of a few days to a few weeks as the maximum. A good choice for the duration of an epoch would then be a week. For crop insurance, the period of the policy is typically some months, so a good choice for the duration of an epoch would be one month.

For each epoch, all policies which are sold in this epoch are handled equally. This step massively reduces complexity.

Core functions of a risk pool

Each risk pool needs to provide a minimum interface to be able to meet the requirements.

Receiving premiums

Each risk pool needs a function that enables the risk pool to receive premium payments. The function may only be called by a registered and approved product contract in a GIF instance. Premium payments can be made in the form of a native token of a blockchain (e.g. xDai on the Gnosis Chain, or ETH on Ethereum Mainnet), or in the form of a stablecoin (e.g. USDC).

Claims payout

Each risk pool needs a function that will payout a claim in case of a loss. The amount of the payout and the decision if a certain loss will trigger a payout is controlled by the product contract. Therefore, this function may only be called by a registered and approved product contract in a GIF instance. The product contract also needs to specify in which token or currency the payout is made.

Receiving investment deposits

Each risk pool needs a function to receive investments. Investments can be made in any currency or token which is specified by the risk pool keeper. Investments need to be registered in the risk pool, so that an investor can always check the status of his investment and the share of profit he makes during his investment.

The risk pool keeper may provide additional requirements from an investor, e.g. KYC. The GIF framework supports the implementation of such requirements, but they are not enforced by the framework — it’s the responsibility of the risk pool keeper to enforce them.

Processing investment withdrawals

No investor wants to invest for an unbounded time, so we need to provide a mechanism that allows withdrawal of investments.

This mechanism is designed in a way that ensures that there are always sufficient funds available to cover losses.

The bookkeeping system which tracks investment deposits and withdrawals is the most complex part of the system.

Processing profit distribution

Part of the premiums paid are used as revenue for investors. Investors lock their capital for a certain period of time and risk losing all or part of their investment. Therefore, a revenue is needed to make an investment attractive.

Profit and revenue need to be distributed among investors in a transparent and fair way, according to the time the funds have been locked, and the risk taken.

The distribution mechanism is another complex process and will be described in the upcoming part two of this tutorial in more detail.

Autonomous control of risk pool parameters

Risk pools vary in size, depending on the demand of the underlying product. We will provide mechanisms that will enable autonomous control of risk pool parameters so the risk pool will reflect increasing demand of the product by increasing the attractiveness for investors, and vice versa.

Therefore, a risk pool can be connected to a product with a feedback loop. Should the demand for a product increase, the risk pool could increase investors’ revenue to make the risk pool more attractive for further investments.

On the other hand, given that there is a lot of capital available, the risk pool could trigger a price adjustment to make the product more attractive on the market.

Conclusion

The core economic process of insurance, the risk transfer between insured and investors, is implemented in the GIF framework via risk pools.

While the standard template for risk pools contains all of the core functionality for processing premiums, claims, deposits, withdrawals, and revenue, the template leaves the maximum flexibility for risk pool keepers to design the economic model of their pool in a way that makes it attractive for insureds, product owners and investors.

Thanks for reading part one of this tutorial on staking and risk pools. Stay tuned for part two by following Etherisc across our social channels including Telegram, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Medium!